Tags: Bribie Island History. Moreton Bay. Brisbane. Queensland. Australia

There are some disturbing aspects of all our history and previous social attitudes that we probably need to be reminded of from time to time. For much of the last century, public feelings and prejudice towards some minority groups were common and acceptable behaviour.

All sorts of people often tried to deny or hide their personal background and heritage. Nowadays anyone who can trace even a slight link to a “Convict” ancestor in Australia now feels proud and keen to let it be known.

That has not always been the case, and it was not until about the 1960s that some people who had tried hard to conceal aspects of their own heritage, began to publicly embrace it.

Who do you think you are?

Modern technology now enables people to discover personal and often tenuous links to distant ancestors who came to this country as Convicts. This is an interesting reversal of “prejudice” in our society. Aboriginal people were also subject to great injustice for many years, despite the fact that they had lived in harmony with this land for countless generations, long before white man came and took it from them.

Aboriginal occupation of this area can be traced back thousands of years to a time before Moreton Bay was even formed when there were no islands, and the coastline was more than 50 km further to the east, on the other side of Moreton Island. This ancient coastline was a recognised pathway for Aboriginal people, and there is much archaeological evidence to support this. When Bribie and the other islands of Moreton Bay were formed by progressively rising sea level over a ten thousand year period, the land was rich and plentiful, providing a variety of foodstuffs from coastal swamps and waterways.

The coastline of Queensland has been the way it is now for only about 1000 years, since sea levels reached their highest point and started receding. Bribie has only been an island for a few hundred years. Matthew Flinders was the first white man to come to Bribie Island and explore Moreton Bay in 1799.

This year marks the 220 year anniversary of that event when he came ashore with his Aboriginal companion Bongaree, after whom the first settlement was named 113 years later in 1912. Bongaree was from the Broken Bay area near Sydney and could not communicate with the local people in their language.

Bribie Island… …a land of Plenty

The indigenous “Joondoburrie” people of Bribie Island enjoyed a rich seasonal diet of plants, animals, and seafood that included kangaroo, possum, goanna, snakes and birds as well as oysters, prawns, crabs and fish throughout the year.

It was indeed an island of plenty that may have supported several hundred people in various seasonal camps around the island and the Passage. With the coming of white man it took less than 100 years for these proud and traditional people to be wiped out. By the 1870’s when pioneer settlers moved into this area, the Indigenous people around the Bay area were eventually reduced to a disparate group of less than 50 people.

This resulted in the first Aboriginal reserve in Queensland being established right here on Bribie Island in 1877, in the area known as White Patch. Under the supervision of Tom Petrie as the visiting Manager they were brought together to grow a few basic crops and were provided with flour, sugar, fishing nets and a small boat to support themselves. Needless to say it didn’t last very long, and within a couple of years funding stopped and it was disbanded.

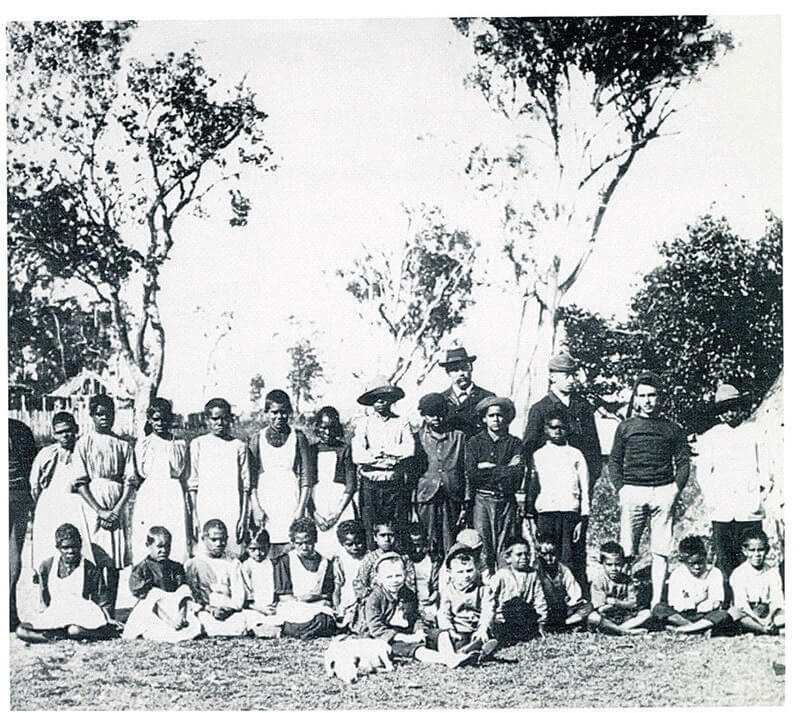

“Mission Point School 1892”

A few years later in 1891 a Mission School was established for local indigenous children at what is now Mission Point, but this too lasted only a short time before being relocated to Myora on Stradbroke Island There was little respect for the few remaining Aboriginal people in those days, but an increasing number of mixed-blood people were even more despised by both the whites and full-blood aboriginals.

Archibald Meston was the Government “Protector of Aboriginals” for this area and in 1891 and he reported that there were very few remaining, and specifically mentioned a lady named Kal-Ma- Kuta from Bribie Island.

This remarkable lady died in 1897 and she was the last of the Joondoburrie people of Bribie Island. Her life story is an interesting one that highlights some prejudices and values from our not very distant past. She had married a white man, Fred Turner, and they lived on the water at Ningi for 23 years where they had 8 children.

Two of their children were at Mission Point School when it closed and the children were moved to Myora. At Christmas time in 1894, just 125 years ago, Fred and his wife wrote a letter to the Colonial Secretary asking for their two children who had been relocated to Myora to be allowed to come home for a few days over Christmas. The request was refused !!

The last of the Joondoburrie.

Fred Turner was the son of William Turner and his mother Eliza, who came out from the UK with two sons in 1862 . Fred was the second son at 8 years of age and had been born in UK in 1854. When Fred grew up he met and fell in love with a local Aboriginal girl named Kal-Ma-Kuta whom he married, and they set up their home at “Turners Camp” on Ningi Creek where she became known as Alma Turner.

They had 8 mixed-blood children, and over the subsequent years all of their children, grandchildren and even some great-grandchildren were taken away from their mothers “for their own good”. During their 23 years living at Turners Camp they were officially responsible for maintaining the navigational Pilot Light on Toorbul Point, where the new Sandstone Point Hotel now stands. Every evening Fred or Alma would walk around the beach to the light, with a bottle of Kerosene balanced on their head, and refill the important navigation light.

Each morning they would walk back and put it out. They did this every day for over 20 years to provide safe passage for the many ships travelling up Pumicestone Passage. Prior to the huge rainfall and floods of 1893, Pumicestone Passage was a major waterway for many vessels travelling to and from Campbellville timber mills on Coochin Creek.

Turners Camp Monument

The Turners home “Camp” site was originally on a small island which years later became part of the mainland when the Military built the road from Caboolture to Toorbul Point in WW2. Alma Turner was a much respected and admired lady, born Kal-Ma-Kuta she died in 1897 as the last of the Joondoburrie people. She was buried in the traditional way and the site marked with a Fig Tree, which later became the resting place for three other descendants, including a box containing the ashes of her daughter Florence who died in 1961.

Florence was one of the daughters who was at the Mission Point School, and was refused permission to go home for Christmas to be with her family back in 1894. Her mother died just three years later in 1897.

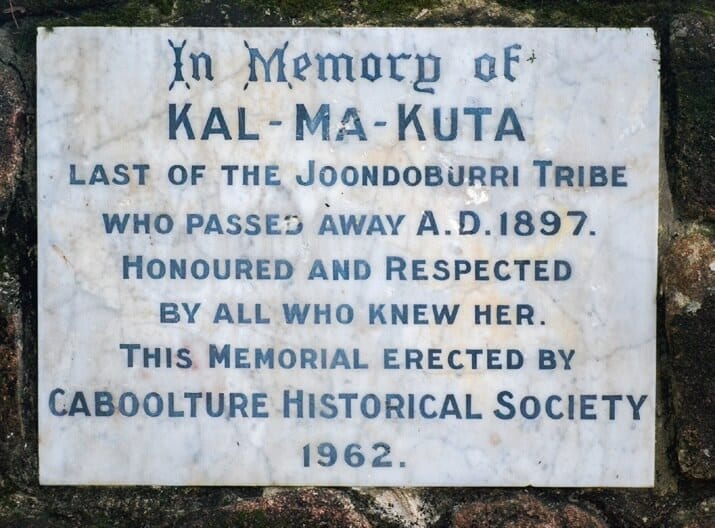

Kal-Ma-Kuta Memorial

However, it took 65 years before Kal-Ma-Kuta was recognised for her remarkable life with Fred and her contribution to the area. The Caboolture Historical Society decided to erect a memorial cairn to tell her story and mark the burial site. Most of the Toorbul Point land had been owned by the Clark family for many years, and had been a military training camp during the War, but a small piece of land was made available for the memorial to be erected.

The new Bribie Island Road had to be constructed as two divided carriageways and the memorial site and fig tree were retained in the centre of the road reserve. The memorial was erected and unveiled in 1962, immediately prior to the completion of the new bridge. The memorial had remained virtually unnoticed for many years but in recent times had been looked after by local taxi owner, the late George Goold, out of respect for this significant aboriginal lady.

Kal-Ma-Kuta Plaque

Kal-Ma-Kuta and her husband Fred started a large family with their 8 children, and today the family tree numbers more than 200 direct descendants. These include great-granddaughters Daphne Dux and Liesha Krause, both of whom have contributed much to local history records. In 2004 Daphne Dux asked the then Caboolture Shire Council to erect a monument at the Turners Campsite.

A wonderful stone carving was commissioned that portrayed the old Navigation Light encrusted with Oysters. However, the wording on the initially erected plaque gave no indication that Alma Turner was in fact aboriginal, and the last of the Joondoburrie people. Such was the public dilemma even just fifteen years ago, in giving recognition to this heritage.

Kal-Ma-Kuta Memorial

A subsequent and additional plaque was later added to correct that omission. The “Turners Camp” memorial sculpture and plaque can be seen on Turners Camp road, a left turn off the Bribie Island Road, just before the Kal- Ma-Kuta memorial. It is an important reminder of the Joonboburrie people who were here long before us.

Bribie Island – A Handy History

The Bribie Island Historical Society has just published a great new book titled “Bribie Island- A Handy History” that has fascinating old photos and brief summary stories about many aspects of local history. It costs just $10 and is available at the Museum and through the Historical Society.

They have monthly public meetings at the RSL Club on the second Wednesday of each month commencing at 6:30 pm. with interesting guest speakers on a wide range of topics, and you can see many more photos and articles on our Blog Site at http://bribieislandhistory.blogspot.com or contact us on [email protected]