Tags: What is Dementia? Can dementia be inherited? Memory changes. Mild cognitive impairment.

DEMENTIA

BY VERONICA MERCER MENTAL HEALTH ACCREDITED SOCIAL WORKER

The reason I chose to discuss Dementia is because we all know somebody who has the insidious disease, or who cares for a loved one with the disease.

What is Dementia?

Dementia is the “umbrella” term for several neurological conditions, of which the major symptom includes a global decline in brain function. The brain function is affected enough to interfere with the person’s normal social or working life.

Dementia affects:

- Thinking.

- Behaviour.

- Ability to perform everyday tasks

- The person’s normal social or working life.

Dementia was a relatively rare occurrence before the 20th century, as fewer people lived to old age in pre-industrial society. It was not until the mid-1970s that dementia begun to be described as we know it today.

We now know dementia is a disease symptom, and not a normal part of ageing.

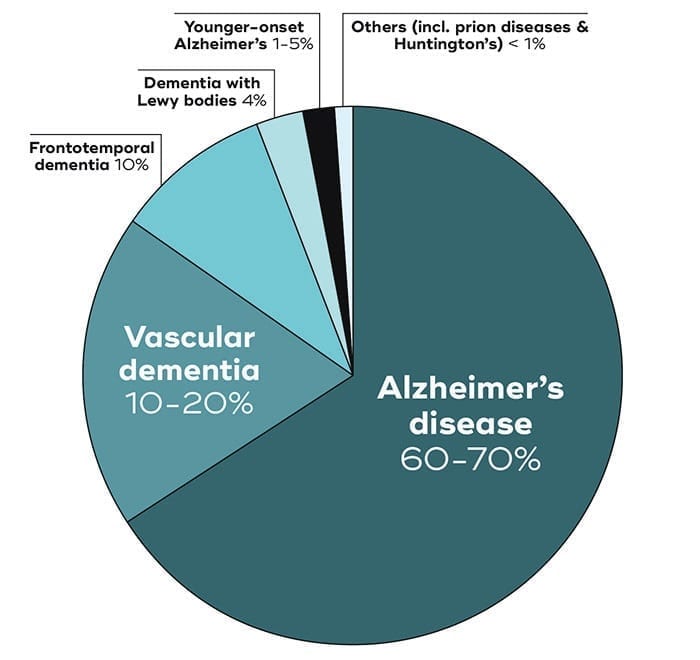

There are over 100 diseases that may cause dementia and the most common include:

- Alzheimer’s disease.

- Vascular dementia.

- Dementia from Parkinson’s disease and similar disorders.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Frontotemporal dementia (Pick’s disease)

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

- Alcohol-related dementia

- Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease

- HIV associated dementia

The Queensland Brain Institute depicts the most common dementias below.

What are the early signs of dementia?

The early signs of dementia are very subtle and vague and may not be immediately obvious. Dementia does require a medical diagnosis. Symptoms include forgetfulness, falling, jumbled speech, or sleep disorder limited social skills and thinking abilities so impaired that it interferes with daily functioning.

People may experience:

- Cognitive: Memory loss, mental decline, confusion in the evening hours, disorientation, inability to speak or understand language, making things up, mental confusion, or inability to recognise common things

- Behavioural: Irritability, personality changes, restlessness, lack of restraint, or wandering and getting lost

- Mood: Anxiety: loneliness, mood swings, or nervousness

- Psychological: Depression, hallucination, or paranoia

- Muscular: Inability to combine muscle movements or unsteady walking

Can dementia be inherited?

This depends on the cause of the dementia, so it is important to have a firm medical diagnosis. Most cases of dementia are not inherited. Some other rare forms of dementia can also be inherited.

These include Huntington’s disease and some forms of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration, where behaviour changes before any change in memory. All these inherited conditions are very uncommon in the general population. One rare form of Alzheimer’s disease is passed from generation to generation.

- This is called Familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD).

- If a parent has a mutated gene that causes FAD, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it.

- The presence of the gene means that the person will eventually develop Alzheimer’s disease, usually in their 40s or 50s.

- This form of Alzheimer’s disease affects an extremely small number of people probably no more than 100 at any given time among the entire population.

- Some other rare forms of dementia can also be inherited. These include Huntington’s disease and some forms of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration, where behaviour changes before any change in memory. All these inherited conditions are very uncommon in the general population.

SOME FACTS

- Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent form of dementia.

- Accounting for 50% to 70% of all cases of dementia.

- It occurs relatively frequently in older people, regardless of family history.

- For females aged 65 to 69 years, dementia affects 1 person in 80 compared to 1 person in 60 for males

- For both males and females aged 85 and over the rate is approximately 1 person in 4.

- Dementia is the second leading cause of death of Australians contributing to 5.4% of all deaths in males and 10.6% of all deaths in females each year.

- In 2016 dementia became the leading cause of death among Australian females, surpassing heart disease which has been the leading cause of death for both males and females since the early 20th century.

- In 2018, there is an estimated 425,416 Australians living with dementia – 191,367 (45%) males – 234,049 (55%) females (dementia.org.au)

- Other risk factors

- A family history of dementia increases one’s risk of developing dementia. This is more likely to do with genetic factors that have not yet been discovered.

- Brain infarcts, heart disease and midlife hypertension increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and Vascular dementia. Smoking has also been identified as a risk factor.

- A study of World War II veterans indicated that moderate to severe head injury increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Another study found that this risk is further increased if the head injury resulted in loss of consciousness.

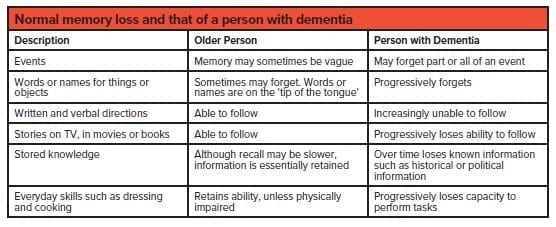

Memory changes

There is a difference between memory loss as a part of normal ageing and as a symptom of dementia. This information describes those differences and provides some tips on keeping your memory sharp.

One of the main symptoms of dementia is memory loss. We all forget things from time to time, but the loss of memory with dementia is very different:

- It is persistent and progressive, not just occasional.

- It may affect the ability to continue to work or carry out familiar tasks.

- It may mean having difficulty finding the way home.

- Eventually it may mean forgetting how to dress or how to bathe.

An example of normal forgetfulness

Is walking into the kitchen and forgetting what you went in there for or misplacing the car keys. A person with dementia however, may lose the car keys and then forget what they are used for.

Key points about normal forgetfulness

- As we get older, the most common change that we complain about is memory change.

- Knowledge of how memory changes as we get older is a lot more positive than in the past.

- Memory change with healthy ageing certainly doesn’t interfere with everyday life in a dramatic way.

- Everyone is different and the effect of getting older on memory is different for each person.

- Recent research describes the effect of getting older on attention processes, on the ability to get current information into storage, on the time it takes to recall things, and “on the tip of the tongue” experiences.

- Research also suggests that immediate memory and lifetime memory do not change as we get older.

Mild cognitive impairment

Memory loss has long been accepted as a normal part of ageing. Recently there has been increasing recognition that some people experience a level of memory loss greater than that usually experienced with ageing, but without other signs of dementia.

This has been termed Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). As MCI has only recently been defined, there is limited research on it and there is much that we do not yet understand.

Behaviour Changes

Dementia affects people in different ways. Common behaviour changes that may occur when a person has dementia, and why these changes occur are explained under the behaviour changes section.

Understanding why someone is behaving in a particular way may help you with some ideas about how to cope. There are many reasons why a person’s behaviour may be changing. Dementia is a result of changes that take place in the brain and affects the person’s memory, mood and behaviour. Sometimes the behaviour may be related to these changes taking place in the brain.

In other instances, there may be changes occurring in the person’s environment, their health or medication that trigger the behaviour. Perhaps an activity, such as taking a bath, is too difficult or the person may not be feeling physically well. Dementia affects people in diverse ways. Understanding why someone is behaving in a particular way may help you with some ideas about how to cope.

Seeking help – where to start

Always discuss concerns about behaviour changes with your doctor, who will be able to check whether there is a physical illness or discomfort present and provide some advice. A doctor will be able to advise if there is an underlying psychiatric illness.

Coping

Coping with changed behaviours can be very difficult and is often a matter of trial and error. Always remember that the behaviour is not deliberate. Anger and aggression are often directed against family members and carers because they are closest. The behaviour is out of the person’s control and they may be quite frightened by it. They need reassurance, even though it may not appear that way.

What to try

- A calm, unstressed environment in which the person with dementia follows a familiar routine can help to avoid some difficult behaviours

- Try to keep the environment familiar. People with dementia can become upset if they find themselves in a strange situation or among a group of unfamiliar people where they feel confused and unable to cope

- The frustration caused by being unable to meet other people’s expectations may be enough to trigger a change in behaviour

- If behaviour becomes difficult, it is best not to attempt any form of physical contact such as restraining, leading them away or approaching from behind. It may be better to leave them alone until they have recovered, or call a friend or neighbour for support

- Try not to take it personally

- Try not to use a raised voice

- Avoid punishment. The person may not remember the event and is therefore

- not able to learn from it

- Speak slowly, in a calm and reassuring voice

- Try not to become provoked or drawn into an argument.

Aggression

This can be physical, such as hitting out, or verbal such as using abusive language. Aggressive behaviour is usually an expression of anger, fear or frustration.

What to try

- The aggression may be due to frustration. Locking the door may prevent wandering, but may result in increased frustration

- Activity and exercise may help prevent some outbursts

- Approaching the person slowly and in full view may help. Explain what is going to happen in short, clear statements such as “I’m going to help you take your coat off”. This may avoid the feeling of being attacked and becoming aggressive as a self-defence response.

- Check whether the aggressive behaviour is about getting what the person wants.

- If so, trying to anticipate needs may help.

Catastrophic reactions

There is a tendency to over-react, which is part of the disease and is called a catastrophic reaction. Sometimes a catastrophic reaction is the first indication of the dementia. It may be a passing phase, disappearing as the condition progresses, or it may go on for some time. Some people with dementia over-react to a trivial setback or a minor criticism. This might involve them;

- screaming,

- shouting,

- making unreasonable accusations,

- becoming very agitated or stubborn,

- or crying or laughing uncontrollably and inappropriately.

- Catastrophic behaviour may be a result of:

- Stress caused by excessive demands of a situation.

- Frustration caused by misinterpreted messages.

- Another underlying illness.

This behaviour can appear very quickly and can make family and carers feel frightened. However, trying to figure out what triggers catastrophic behaviour can sometimes mean that it can be avoided.

Hoarding

People with dementia may often appear driven to search for something that they believe is missing, and to hoard things for safekeeping. Hoarding behaviours may be caused by:

- Isolation – When a person with dementia is left alone or feels neglected, they may focus completely on themselves. Hoarding is a common response.

- Memories of the past – Events in the present can trigger memories of the past, such as living with brothers and sisters who took their things or living through the depression or a war with a young family to feed.

- Loss – People with dementia continually lose parts of their lives. Losing friends, family, a meaningful role in life, an income, and a reliable memory can increase a person’s need to hoard

- Fear – A fear of being robbed is another common experience. The person may hide something precious, forget where it has been hidden, and then blame someone for stealing it What to try

- Learn the person’s usual hiding places and check there first for missing items

- Provide a drawer full of odds and ends for the person to sort out as this can satisfy the need to be busy

- Make sure the person can find their way about, as an inability to recognise the environment may be adding to the problem of hoarding

Repetitive behaviour

People with dementia may say or ask things over and over. They may also become very clinging and shadow you, even following you to the toilet. These behaviours can be very upsetting and irritating. What to try

- If an explanation doesn’t help, distraction sometimes works. A walk, food or favourite activity might help

- It may help to acknowledge the feeling expressed. For example, “What am I doing today?” may mean that the person is feeling lost and uncertain. A response to this feeling might help

- Do not remind the person that they have already asked the question

- Repetitive movements may be reduced by giving the person something else to do with their hands, such as a softball to squeeze or clothes to fold.

Tips for keeping your memory sharp

There is no prevention or cure for dementia. However, here are a few tips for keeping your brain fit and memory sharp:

- Avoid harmful substances. Excessive drinking and drug abuse damages brain cells.

- Challenge yourself. Reading widely, keeping mentally active, and learning new skills strengthens brain connections and promotes new ones.

- Trust yourself more. If people feel they have control over their lives, their brain chemistry improves.

- Relax. Tension may prolong a memory loss.

- Make sure you get regular and adequate sleep.

- Eat a well-balanced diet.

- Pay attention. Concentrate on what you want to remember.

- Minimise and resist distractions.

- Use a notepad and carry a calendar. This may not keep your memory sharp but does compensate for any memory lapses.

- Take your time.

- Organise belongings. Use a special place for unforgettable, such as car keys, and glasses.

- Repeat names of new acquaintances in conversation.

- The impact of dementia upon families, carers and society is huge.

- In 2018, dementia is estimated to cost Australia more than $15 billion.

- By 2025, the total cost of dementia is predicted to increase to more than $18.7 billion in today’s dollars, and by 2056, to more than $36.8 billion.

- Dementia is the single greatest cause of disability in older Australians (aged 65 years or older) and the third leading cause of disability burden overall.

- People with dementia account for 52% of all residents in residential aged care facilities

- There are approximately 200,000 Australians providing unpaid care to a person with dementia.

- Nearly a quarter of people with dementia living in the community (22%) rely solely on informal care and do not access any formal care services.

- 81% of co-resident informal carers provide more than 40 hours of care per week.

- These carers are often the spouse or child of the person and provide wide-ranging support, including helping the person with dementia with activities of daily living, personal care, and managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

- It is the carers who are having to make tough decisions about treatment options, use of services, finances, and long-term care. Some carers have work, children and other family commitments to cope with as well.

- Caring for a person with dementia can lead to increased rates of depression, stress and anxiety compared to non-carers

- In Australian surveys of carers, 31% of respondents reported that caring for the person with dementia had a negative impact on their physical health (3), and 34% reported feeling weary or lacking in energy.

- The stress of caring may result in impaired immunity, elevated levels of stress hormones, hypertension (high blood pressure) and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

- The demands of caring for someone with dementia have been shown to put carers at risk of social isolation.

- Caring also has a significant fiscal impact. According to the Dementia in Australia report, 54% of carers of people with dementia (and 45% of primary carers) are of working age (1). However, only 56% of these (and 38% of primary carers) were employed at the time of the survey.

Tips for living with Dementia

Agree – never argue. Redirect – never reason. Distract – never shame. Reassure – never lecture. Reminisce – never say remember. Ask – never command. Repeat – never say “I told you so”. “I have Dementia. My eyes do see. My ears do hear, I am still me, so let’s be clear. My memory may fade, my walk may slow. I am me inside, don’t let me go.” – Unknown Wishing you all good mental well-being – Veronica.

Other Articles

https://thebribieislander.com.au/about-autism/