Bribie Island’s most famous resident lived a solitary life in a grass hut in the Bribie bush for 21 years before his death in 1974. His works now hang in Art Galleries around the world. Books have been written and films made about his amazing life, and there is a permanent display at the Bribie Museum. This was Ian Fairweather. Another famous and more recent Bribie artist also has works in galleries around the world, is better known locally for his huge, recently refurbished, Welcome to Bribie Mural that stands near the bridge.

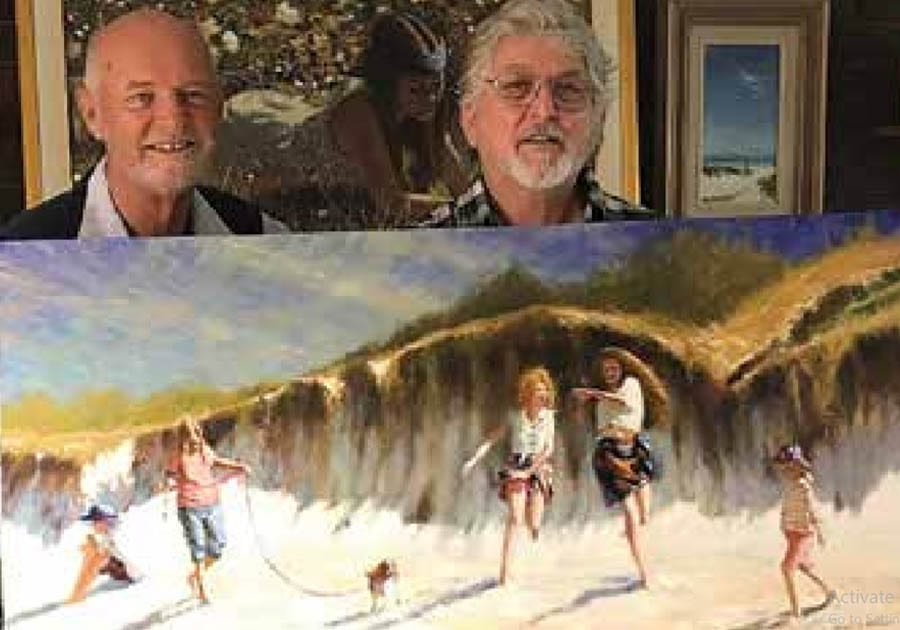

The artist is Dale Marsh. When the Bribie Seaside Museum opened ten years ago the big Welcome Mural was replaced with a Fairweather painting for a while to promote the new Museum.

As a young man back in the 1950s and 60’s, Dale Marsh spent time with Ian Fairweather in his Bribie hut and later painted his famous portrait just days before he died.

Dale Marsh recently invited me to visit him at his Studio at Kurwongbah where he shared some vivid memories of time spent with Ian Fairweather, and stories of his Bribie childhood more than 70 years ago.

The life and memories of these two remarkable artists will be told in two parts.

This article is Part 1 and tells of their initial meeting.

IAN FAIRWEATHER

Ian Fairweather lived and painted on Bribie Island over a period of 21 years from 1953 until he died in 1974.

Born in Scotland in 1891, the ninth and youngest son of a military doctor, he was raised by two maiden aunts, while the rest of his family lived in India. He joined the Army in 1914, was captured on the first day of World War I, and spent four years in prison, despite five attempts to escape.

In 1920’s he studied at the Slade Art School in London, then travelled extensively in Canada, China, South East Asia & India, where he again joined the Army as a Captain in World War 2.

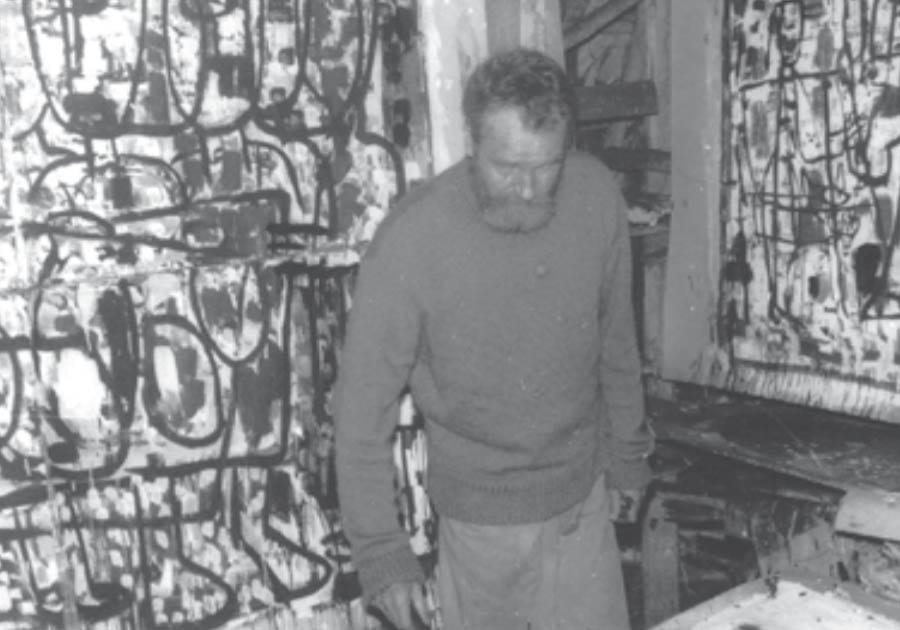

After the war, he was jailed in Indonesia as a suspected spy after sailing a homemade raft from Darwin to Timor. He was lucky to survive that adventure. Ian Fairweather came to the quiet of Bribie Island in 1953, seeking a lifestyle of isolation, and a chance to live life and paint in his own unique way He built a Polynesian style grass-hut, with a thatched roof and earth floor, where he lived and painted, and pursued his interest in Oriental studies and Chinese translation.

The international art world had long since recognised his talent, but Bribie Islanders saw little of him and even less of his unusual work. He was seen as a weird and unhealthy hermit, living in the bush, without power or water, at one with nature, and keeping to himself. He lived close to the rubbish tip, the source of many of his painting surfaces, and after 21 years of this unusual lifestyle, and in declining health, he died in 1973 at the age of 83.

DALE MARSH

Was born in Brisbane in 1940 and has lived and visited Bribie Island most of his life. Many exhibitions of his work have been held throughout the world, prestigious Awards won, and books about his life and works have been published. Bribie scenes feature in much of his work hanging in major Art galleries.

Dale continues to paint at his bush hideaway in Kurwongbah, and a recent exhibition Bribie Museum showed many remarkable paintings. His huge “Welcome to Bribie” mural by the bridge has recently been refurbished, and during my recent visit, he showed me the painting he offered as a replacement for the Welcome to Bribie Mural.

MARSH met FAIRWEATHER in 1954

The following words are some of the memories Dale Marsh shared with me, as he reflected on the impact of his relationship with Ian Fairweather, after meeting him almost 70 years ago…

I was obsessed with painting and drawing as a child, the passion didn’t die out in me as it does with most kids, but instead continued to build all through my teenage years. When I was about 14 years old I was still working in watercolour from a little paint box I would carry about with me. At about this time I heard from my Aunt that the famous painter Ian Fairweather had come to live on Bribie Island.

“He’s an old hobo with a bushy beard and long matted hair and he lives in the bush in a bark humpy just in from the Bongaree end of the main island road. He won’t talk to anyone and when he goes to the little Bribie cinema in the church hall, no one will sit near him because he smells.” Such was the local opinion at that time of one of Australia’s most prominent artists.

I was intrigued. In the depths of my secret soul, this was how I would have preferred to live too. I disliked suburbia intensely and longed to live away by myself in some peaceful place where no one would bother me, but felt powerless to change.

With the prospect of a real artist nearby, I desperately wanted to meet him, so one morning I gathered my watercolours and set off to meet the man that was so famous, that the Courier Mail had written stories about him.

I found the tree archway that was the entry to Fairweather’s place and at the end of a sandy track, hidden away amongst a clump of Bribie pine trees stood two bark huts. There was nothing to knock on so I called out his name several times. The door opened, and Ian Fairweather stood at the entrance. I introduced myself, said I was an aspiring painter and proceeded to show him my watercolours. Simple plain subjects of sailboats, trees, sand dunes and beaches. He looked carefully at each one and finally shook his head, turned his blue eyes full on me and said in a gentle voice, “I don’t understand them”. This bewildered me. As far as I knew, there was nothing to understand in my simple pictures.

He then invited me into the bark hut to look at his paintings. Just inside the doorway was a huge carpet snake. “Step over the snake” he said, “He’s digesting a possum”. The interior of the hut was chaos. There along one wall was his bed made from tee tree saplings, raised off the ground probably because of snakes. There was a shabby small table with two chairs that looked as though they had been reclaimed from a tip.

The light streamed in through a panel of translucent plastic in the roof stretched between two logs, and gave an eerie glow to the interior. Another bench was jam-packed with half-used tins of house paint in a variety of colours, and jam jars of old brushes encrusted with paint. On another bench stood a welldaubed plywood panel with paintings pinned to it. Those paintings were a revelation of colour, form, and a curious sort of primitive spiritual strength. I felt shivers go up to my spine to the top of my head. There on that studio wall were the forms of the bracken fern and twisted tree shapes that were part of that environment. It captured the essence of the island that I was always aware of. A spiritual thing, I could always feel it, was aware of it. You felt close to it, especially where the Bribie pines grew.

I called it the spirit of Bribie. The forms in the paintings combined with the quiet colour harmonies soared high with the intensity of an angelic choir. There were no recognisable objects anywhere in his pictures. This shocked me. Just shapes, coloured forms, and lines that snaked through the composition. It was my first encounter with abstract art. I simply said to him “I don’t understand them”.

My own modest pictures now seemed to me so empty and simplistic. The experience peeled my eyes and I saw for the first time the really enormous and profound potential of painting. I think it was the man’s calmness that fascinated me most of all. There seemed to be a great mystery about him, a deep serenity that radiated all about his person. Even his environment, the huts, and the sweet-smelling pine grove emanated this quality. He possessed a quiet dignity quite rare in human beings, as though his mind was a lake of perfectly still water without the slightest ripple. In conversation, the power of his intellect amazed me. There was such an incongruity between what he said and the gentle way he spoke and his physical appearance. He looked like a hobo. Long unkempt hair, bushy beard, wearing dirty old pyjamas in the daytime. His toenails grew out from his unwashed feet and curled around underneath his feet making it difficult for him to walk.

He spoke of the hardness of his life, always travelling in foreign countries, always in poverty, and always the outsider. We talked for a time about art and life then I felt I had already taken up too much of his time. I should go and let him get on with his work. Actually, my heart was bursting with newfound inspiration I needed to get away and express it all in a painting. Even after I had left and headed home, something of his serenity stayed with me a while. I did not revisit Fairweather for the rest of that holiday, did not feel I should take up his time, but for every subsequent year, I came to the island I would always call on him. I was never quite sure if he remembered me.