It’s a bad start to our first meeting in Austria in 1969, interviewing novelist screen writer-director-producer of KING RAT, TAI-PAN, SHOGUN and NOBLE HOUSE fame, JAMES CLAVELL. Each novel is an instant bestseller and all, in the 70s and 80s, will be released globally as movies or TV series with a 120 million audience. But I find James arrogant, condescending, dismissive, and yes, in fact, quite rude. And interviewing him is as fruitful as trying to penetrate the skin of an armadillo.

Two years later, the LONDON OBSERVER also ask me to interview James in London, and this time I am prepared to retaliate. But instead, James’ welcome, friendliness, and courtesy leave me both speechless and angry. “Why are you so nice to me today, when you treated me abominably in Austria last time we met?” I blurt out indignantly. James pauses, shrugs his shoulders, and, with a guilty smile, his brash, but honest reply makes me laugh. “You’re the Observer now!”

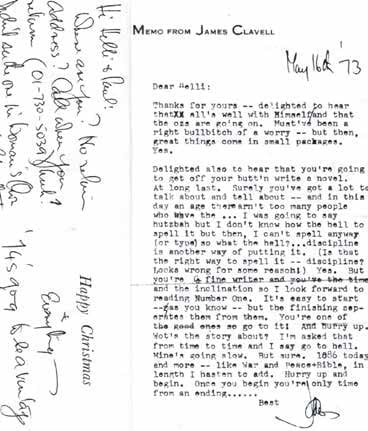

And so a curious friendship develops with a most inspirational and superb writer, but a man I could never imagine wanting to be friends with. When my son is born in 1973, weighing just over two pounds and being 12 weeks premature, even a flowerpot of hydrangeas arrives from James on my London hospital bedside table. This flowering bush grows 2m high in my garden, when, in 1980, I leave London, returning to Australia after completing my pilot licence on the Isle of Guernsey.

But in 1971 we are sitting in a small London office, cluttered to the ceiling with files, books, parcels, papers, and posters. James has just finished his latest production with all offices, administrative staff, and paperwork completed, but is tidying up the last remnants himself, as he explains. “You pull in your tentacles from five offices and I’m now running my empire from behind this miserable curtain.

It drives me barmy. Instead of being able to go dream a bit, I’m doing the work of a 20-pounds-week clerk and am trying to be a businessman, which I’m not.” Although he now owns homes in L.A., Vancouver, and London, 50-year-old James insists there is no time to live in any of them, as he is always on location. And I am not the only person finding this Australian born, half-Irish HELLY’S CELEBRITIES OF THE 20TH CENTURY with Scottish overtones Englishman with American citizenship, difficult. James likes being the boss and he is not the most loved man in the film industry.

On film sets, you can feel the tension between James, his actors, and his crew. To the charges of being cold, hard, ruthless and ready to kill, he responds to me with glee. “I’d like to spread that around a bit. It’s a great reputation. I’m not really trying to be the favourite man in the business. What I am concerned about is getting the best out of people.” But does he??

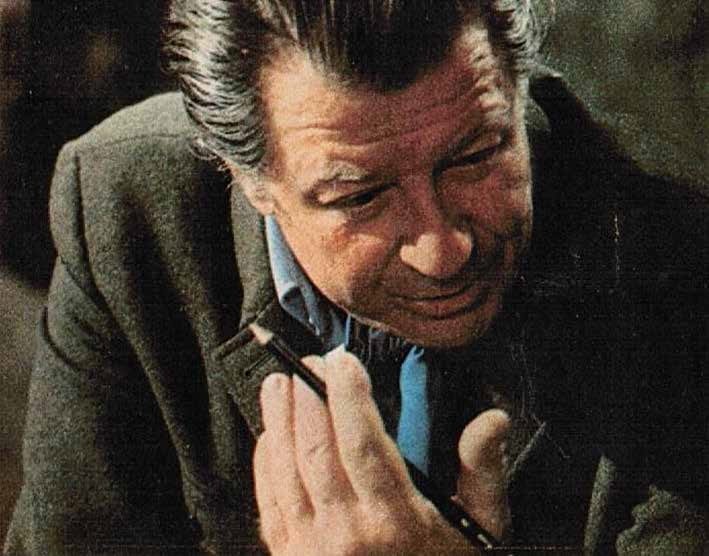

As screenwriter and director, he certainly achieves this in the 1967 TO SIR WITH LOVE, starring Sidney Poitier, Katharine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracey, as well as being co-writer for 1963 THE GREAT ESCAPE with Steve McQueen. As a director it is clearly the exercise of power which traps James. “It’s certainly not material success,” he agrees. “After a very small threshold, once you have your drop-dead money, wealth is just a point of view.” Longish, greyish hair falls over James’ ears, as the genius bends forward on his desk and having made his point with relish, he straightens up, his strange blue eyes narrowing, and he drops a clenched fist on the desk.

You are suddenly conscious of the former Captain in the Royal Artillery, as he was in World War II, captured in 1942 by the Japanese in Java and incarcerated in the infamous Changi Prison in Singapore, where only 1 prisoner in 15 survived – the setting of his first novel, KING RAT. But in 1971 the real challenge for James, who will succumb to cancer in 1994, is the actual writing not the directing. “I’m a soul stealer, a story-teller. I wanted to be a director because a director is a writer in the film form.

The director is the story-teller. But it’s time for another book now – some real work. It means cutting myself off completely from what I’m doing. I’ve told everybody. Eventually, they’ll believe me. “Writing is the hardest work I know and it stretches me the most. The greatest satisfaction has known has been in my novels. If you write the truth, you’re fulfilling your function. But my truth is not necessarily yours.”

Other Articles

- HELLY’S CELEBRITIES OF THE 20TH CENTURY – GLENDA JACKSON

- HELLY’S CELEBRITIES OF THE 20TH CENTURY – SAMMY DAVIS JNR