It’s the song that changed John Schumann’s life. But when the singer-songwriter sat down to write about the Vietnam War more than 30 years ago, he never dreamt the song would become a number one hit, or that its lyrics would one day be inscribed on a national memorial.

“It’s also a song that you can’t perform lightly. It means so much to other people … you have to concentrate and play it with sincerity and intensity every time you play it … [but] in lots of ways it doesn’t belong to me, it belongs to the people about whom it’s written.”

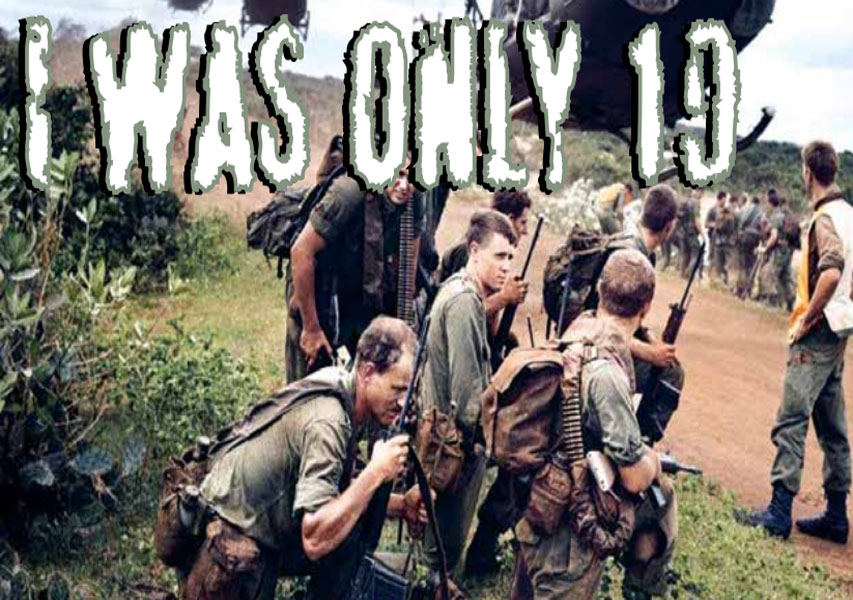

He decided to write a song for the veterans, but he didn’t want to base it on media reports and his imagination. When Cold Chisel recorded Don Walker’s Khe Sanh, he thought he’d missed his chance, but then he wrote I was only 19, based on the experiences of his brother-in-law, Mick Storen, who had served with 6 Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) in Vietnam in 1969. “I was going out with Denny at the time, and I knew her brother had been in Vietnam, but she told me that he didn’t talk about it,” Schumann said. “She brought him along to hear the band play at the Oxford Theatre in Unley [shortly before Christmas in 1981], and we all went out for a drink and something to eat after the show … Notwithstanding the fact that I’d been warned that he didn’t talk about it, I asked him – very possibly on the wings of a six pack – if he would be prepared to talk to me.”

Much to Schumann’s surprise, Storen said yes. But there were two conditions, the first being that Schumann didn’t denigrate Storen’s mates. “That was not what I wanted to do, so that was easy,” Schumann said. “And the other condition was that he heard the song first, and if he didn’t like it, then the song was not to see the light of day.” Schumann agreed, and the pair met a few months later at Denny’s house in the Adelaide Hills. “He came up one night, and we had a long conversation, which I taped on cassettes, and I just listened to those cassettes over and over and over,” Schumann said.

When he sat down to write a few months later, the words just tumbled out. “It was like it’d already been written,” Schumann said.

He admits it was “pretty scary” playing the song to Storen for the first time. “He’s not very demonstrative at the best of times, but he did greet the song with silence, and not unreasonably, I thought that I’d really put my foot in it,” Schumann said. But no, he liked it, and I was so apprehensive about the whole thing, I just remember he said, ‘Mate, you’d better go see Frankie.’ And he said that a few times.”

In the original lyrics, Schumann wrote that Tommy “kicked a mine the day that mankind kicked the moon”, but Storen didn’t know any Tommy’s and wanted the name changed. It was Storen’s platoon commander, Lieutenant Peter Hines, who stepped on the mine in July 1969, but Storen didn’t want his name used out of respect for his family. He told Schumann, “You can use Frankie, but you’d better go and see Frankie to ask him if it’s okay.”

Frankie was Frank Hunt. He had been badly wounded in the same incident that killed Hines, and in January 1983, Schumann went to visit Hunt at his home in Bega. “I knocked on the door, and I don’t think he was very impressed,” Schumann said. “I was this long haired, bearded, left-wing firebrand … but because I was a friend of Mick Storen’s, he let me in the house, and I played him the song, and he was knocked sideways too. He just wanted to hear it again and again, and I was sick of playing it by this point, so I asked him if could just record the song into his ghetto blaster.” Frankie agreed to share his story, and when the song was released in March 1983, the impact was immediate. “Everybody I played it to was knocked out by it,” Schumann said.

The song went to number one, and four years later 25,000 Vietnam veterans marched through the streets of Sydney in a belated welcome home parade. For the hundreds of thousands of Australians who bought the record, Schumann suspects it was a way of saying sorry.

“I think I was only 19 provides an ‘I get it’ moment,” Schumann said. “Australians are fundamentally fair and decent, and I think I was only 19 was a story … that made us stop and think, ‘Oh, shit, we didn’t do the right thing by those blokes.’ It gave us all a chance to look over the fence and look into the backyards of the Vietnam veterans who lived next door or down the street.

I think we’ve learned to separate our position on the war and our position on the men and women who are sent to fight it. And I think that’s a very important distinction.” Thirty-five years later, veterans still approach Schumann to thank him for telling their story and helping their families understand.